The Rockwell Files: What Norman Rockwell means to George Lucas and Steven Spielberg

The story of how the great American illustrator inspired the great American filmmaker — and his best friend.

George Lucas made headlines last week when he made a generous $1.5 million donation to the Norman Rockwell Museum, a shrine to the eponymous illustrator and painter who was best known for his contributions to The Saturday Evening Post over the course of four decades.

The grant will help the Stockbridge-based museum to take Rockwell's work on tour, and enable the museum to create new multimedia experiences for visitors and populate an online media hub with podcasts and lectures.

"This is a truly transformational grant," museum director Laurie Norton Moffatt said in a release. "We are deeply grateful to George Lucas for supporting our commitment to students, teachers, and life-long learners everywhere, connecting them with Norman Rockwell's legacy in new and compelling ways."

The grant is just the latest step in Lucas' longtime love affair with Rockwell. In 2013, he bought Rockwell's Saying Grace at auction for a record $46 million.

His first Rockwell, Boy and Father: Baseball Dispute, was his first big purchase after the success of Star Wars.

His best friend, Steven Spielberg, couldn't believe Lucas had "a living, breathing oil painting by the hand of this great American icon".

"It was amazing," Spielberg once told CBS. "I went out and I got a bigger Rockwell!"

Since then, Lucas and Spielberg have collected Rockwell paintings and sketches the same way their fans might collect Star Wars trading cards.

The duo's mutual love of Rockwell has been a key component of their legendary bromance, which began when Francis Ford Coppola introduced them backstage at a student film festival at UCLA in 1967.

They met again in the early '70s, when Lucas was in LA to cast American Graffiti. Lucas was staying at the ramshackle Benedict Canyon address that he'd once called home while he attended USC's film school.

A group of young filmmakers and cinephiles were also staying at the address, including Spielberg, who was working on the script for his first feature, The Sugarland Express.

Lucas would come home after casting all day, and he and Spielberg would talk, soon becoming fast friends.

Their mutual affinity for Rockwell makes sense, when you consider he was also a populist artist who had no trouble connecting with audiences, but wasn't always taken seriously by highbrow critics.

"You know, so many artists have a tendency to paint without emotion, without any connection to the audience," Lucas told CBS. "And both Steve and I are die-hard emotionalists, and we love to connect with the audience."

Rockwell was famed for his ability to tell an entire story with a single image. For Lucas, his love of Rockwell is part of a larger interest in "narrative art" — he famously plans to place his collection of American illustrative art on display in his own museum, although his efforts have been stymied so far.

He and Spielberg have placed their Rockwells on display once before, though. In 2010, the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC hosted Telling Stories, an exhibition of 57 Rockwell pieces from their collections.

"There's a different lens for looking at Rockwell because of how George and Steven see their pictures," curator Virginia Mecklenburg told the LA Times. "They are both drawn to Rockwell's stories — the way an entire narrative unfolds because of how he crafts a single frame."

Both men first came across Rockwell's work through his Saturday Evening Post covers.

"I grew up in the heyday of the Post magazine," Lucas told the Smithsonian American Art Museum's Eye Level blog.

"We subscribed and every week or so we'd get a picture in. I would enjoy it and I became a fan of illustrators. I liked drawing, I liked art, and I especially liked magazine illustration and comic illustration. So that was my first introduction to art in general. And then as I went on I took history of art and a lot of other things that broadened my range of art appreciation, but at the same time my heart stayed with illustrators."

Lucas' interest in illustration, honed by drawing pictures of his beloved fast cars as a teen, even led him to pay the rent for a summer of living away from home in Malibu by selling his own paintings of "large-eyed beach bunnies".

That's what sold, anyway, but he told the LA Times his true interest lie in angst-ridden portraits of "morose, Giacometti-style, dark-eyed, struggling suffering people" that were not as commercial. (Even in his teens, then, Lucas was feeling the pull between his populist, commercial instincts and his interest in "experimental" work with no mass appeal.)

After he graduated from high school in Modesto, California, Lucas planned to go to the Art Centre in Los Angeles — but his father, the real-life Lars Owen to Lucas' real-life Luke Skywalker, refused to pay for it. "My father didn't want to have an artist in the house, so I ended up going into anthropology instead," Lucas told Eye Level.

Lucas eventually transferred to USC's film program — but he would always maintain an interest in both illustration and anthropology, and he credits Rockwell with that as much as anybody.

"I've always been interested in anthropology, and I've always been interested in art that speaks to the time in which it was made," Lucas told Eye Level. "As somebody that records a time, I think [Rockwell was] brilliant at it. Because it's not just recording it, he captures the emotion and more importantly the fantasy, the ideal, of that particular time in American history.

"So you really get a sense of what America was thinking during those years and what their ideals were, and what was in their hearts."

Ultimately, it's that idealism — the sense that "this isn't the way things were, it's the way things should have been" — that most appeals to Lucas about Rockwell's work.

"For me, the interest is mythological," he told the LA Times. "There's the myth of patriotism, the myth of religion, the myth of America as a wonderful, bucolic place where everyone is created equally and good people succeed. Rockwell taps into our best aspirations for ourselves."

If there's one thing that ties Lucas' work with Rockwell's, beyond their ability to tell a story visually, it's a certain innocence and naiveté.

"That idealism, that naiveté, that innocence is Norman Rockwell," Lucas told Eye Level.

Spielberg, funnily enough, once described Lucas the same way. The first time Lucas showed a rough cut of Star Wars to his peers, the screening was a disaster — and only Spielberg had faith that the movie would be a hit.

"That movie is going to make $100 million and I'll tell you why," he told the naysayers. "It has a marvelous innocence and naiveté in it, which is George, and people will love it."

At one stage of his life, Lucas could have been the child depicted in Rockwell's Boy Reading Adventure Story, and he arguably spent most of his career telling stories to that boy.

"On the one hand, [Star Wars is] a film for young people, a film for 12-year-olds that taps into the Norman Rockwell world of bold adventures," Lucas told the LA Times. "But then, on the darker side, it explores the psychology of our relationships with our parents, our government and some things not at all Rockwellian."

While Spielberg's collection consists mostly of Rockwell's completed paintings, Lucas' consists largely of sketches — perhaps a reflection of his belief that no piece of art is ever really finished.

"With Rockwell the pencil sketches are as illuminating and as interesting as the paintings," he told Eye Level. "Sometimes even more interesting. He simplified his style very much during the 1960s and late '50s, and I like his earlier works, and I like the sketches of the later works because they have much more detail in them, and they're much more elaborate."

In some cases, Lucas owns the sketch and Spielberg owns the finished painting, and they were able to bring them together for their joint exhibition.

One of those works, Happy Birthday Miss Jones, demonstrates a belief of Lucas' that would help make the Star Wars universe feel so full of life.

"I like the craftsmanship of the sketch, but the actual painting itself demonstrates that with Rockwell, every person is a character, which is what we always aim for in the movies," Lucas told Eye Level.

"We have to make sure that the extras and everybody that's on the screen has a personality, a life. They aren't just nameless, faceless drones that walk through the shot. And a lot of artists don't bother with that."

For Spielberg, one Rockwell piece — Boy on a High Dive — talks to him louder than any other.

"I've always loved that painting. It means a lot to me, because we're all on diving boards hundreds of times during our lives, taking the plunge or pulling back from the abyss," Spielberg told Eye Level.

"For me, that painting represents every motion picture just before I commit to directing it. Just that one moment, before I say, 'Yes, I'm going to direct that movie'. For Schindler's List, I probably lived on that diving board for 11 years before I eventually took the plunge. So that painting spoke to me the second I saw it.

"When I saw that the painting was available to add to my collection, I said, 'Well, not only is it going in my collection, but it's going in my office so I can look at it every day of my life'."

Spielberg even placed a Rockwell work in one of his films. In Empire of the Sun, a young boy (played by Christian Bale) is put to bed by his parents in a scene that recalls Rockwell's Freedom from Fear — and later in the film, we see that the boy keeps a reproduction of the painting itself during his captivity in a prison camp.

Ironically, of all the films with John Williams scores that established the foundation for the modern blockbuster in the '70s, the most Rockwellian is the only one Spielberg and Lucas had nothing to do with — Richard Donner's Superman: The Movie, with its idealised depiction of Smallville.

Sadly, Rockwell didn't have a chance to see the extent of his influence on these two titans of American cinema, or to reflect their impact on pop culture in his own work — his last work was 1976's Spirit of 76, and he died of emphysema in 1978.

He did live on, though, in an episode of Lucas' Young Indiana Jones Chronicles. A young Rockwell was portrayed by actor Lukas Haas in the episode Paris, September 1908, in which Rockwell produces a sketch in the style of one of Pablo Picasso's works that is so good, Picasso claims it as his own — the ultimate validation, albeit fictional, for an artist that had so often been looked down upon by the critics that lined up to praise Picasso.

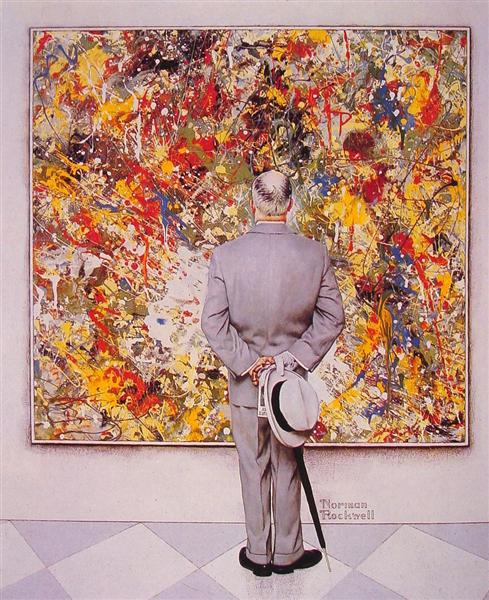

This might also have been a nod to a real Rockwell work, The Connoisseur, that required the illustrator to ape Jackson Pollock's abstract expressionist style.

If Rockwell had been a filmmaker, he might have created slices of Americana capable of standing up against the likes of American Graffiti and E.T. — but Spielberg is glad he didn't.

"I think if he had been a filmmaker, he'd have been a great filmmaker, and he would have been a famous filmmaker," Spielberg told Eye Level.

"But thank God he wasn't a filmmaker; thank God he painted pictures to inspire other filmmakers to do better work. I think that's what Rockwell has done for all of us who love him and appreciate his paintings. He has made us better artists."

All images via WikiArt

Force Material is a podcast exploring the secrets and source material of Star Wars with hosts Rohan Williams and Baz McAlister. Listen and subscribe on iTunes, Spotify, iHeartRadio, TuneIn, Stitcher, PlayerFM and Castro; stay in touch with us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram; and support the show by browsing our range of shirts, hoodies, kids apparel, mugs and more at TeePublic.