The ‘70s porn parody that beat George Lucas to the punch

How a group of pornographers and special effects legends brought a Flash Gordon pastiche to the big screen three years before George Lucas.

1974’s Flesh Gordon opens with Earth in peril (kind of) — ‘sex rays’ from the planet Porno are bombarding the globe, turning everyone into nymphomaniacs.

Football star Flesh Gordon and his girlfriend Dale Ardor, the only survivors of a plane crash caused by the sex rays, team up with a scientist, Dr Flexi Jerkoff, to travel in his very phallic space ship towards the source of the rays.

There, they have to overcome Penisauruses, Robosapiens and buxom Amazonian lesbians in order to confront the evil galactic emperor, Wang the Perverted.

With a little help from Wang’s daughter, Queen Amora, and the effeminate Prince Precious and his forest tribe, they reach the dastardly Wang. But the mad emperor has one last trick up his sleeve, as he awakens the giant Great God Porno to give our heroes a distinctly unhappy ending…

When George Lucas made Star Wars, he never tried to hide the influence of Flash Gordon on his film.

“I loved the Flash Gordon comic books,” he told American Film in 1977. “I loved the Universal serials with Buster Crabbe. After THX 1138 I wanted to do Flash Gordon and tried to buy the rights to it from King Features, but they wanted a lot of money for it, more than I could afford then. They didn’t really want to part with the rights — they wanted Fellini to do Flash Gordon.

“I realised that I could make up a character as easily as [Flash Gordon creator] Alex Raymond, who took his character from Edgar Rice Burroughs. It’s your basic superhero in outer space. I realised that what I really wanted to do was a contemporary action fantasy.”

Lucas saw Star Wars as a return to the optimistic adventure fiction of his youth.

“It struck me that we had lost all that — a whole generation was growing up without fairy tales,” he told American Film. “You just don’t get them anymore, and that’s the best stuff in the world — adventures in far-off lands. It’s fun.

“I wanted to do a modern fairy tale, a myth. One of the criteria of the mythical fairy tale situation is an exotic, faraway land, but we’ve lost all the fairy tale lands on this planet. Every one has disappeared. We no longer have the Mysterious East or treasure islands or going on strange adventures.

“But there is a bigger, mysterious world in space that is more interesting than anything around here. We’ve just begun to take the first step and can say, ‘Look! It goes on for a zillion miles out there.’ You can go anywhere and land on any planet.”

Like Lucas, the makers of Flesh Gordon — director and producer Howard Ziehm, with co-director Michael Benveniste and co-producers Walter R. Cichy and Bill Osco — saw Flash Gordon as being emblematic of a type of adventure story that just wasn’t being told anymore; as an antidote, of sorts, for a cynical society.

They just got there three years earlier, and they weren’t as subtle about it.

While Lucas made sure to scratch the Flash Gordon serial numbers off, to make Star Wars its own entity with its own distinct characters, the makers of Flesh Gordon blatantly lifted the plot, characters, and a number of scenes and shots from Universal’s original 1936 Flash Gordon serial, simply giving the existing work a porn paintjob.

The planet Porno is, of course, Mongo; Dale Ardor is Dale Arden; Wang the Perverted is Ming the Merciless; Dr Flexi Jerkoff is Dr Alexi Zarkov; Wang’s daughter Amora is Ming’s daughter Aura; and Prince Precious is Prince Barin.

It was all so similar that, according to Howard Ziehm’s DVD audio commentary, Universal Studios actually planned to sue his production company, Graffiti Productions, for plagiarism. (Graffiti Productions, incidentally, was founded in the late ‘60s, years before Lucas released American Graffiti in 1973.)

To avoid a lawsuit over the Flash Gordon serial, Ziehm agreed to add the disclaimer “Not to be confused with the original Flash Gordon” to all the film’s advertising materials (including the trailer), and added an opening crawl to the film that established that it was a parody.

From 1929 to 1933 America had been ravaged by a merciless depression. The public needed something to help lift morale and give courage. One of the greatest morale builders was the creation of the super hero: Flash Gordon, Captain Marvel, Buck Rogers, Superman and many others. They possessed the goodness and moral fortitude which the country could admire in its time of need.

In today’s troubled times, we, the producers, felt there existed a need for more entertaining humour. Realising America’s respect for things of the past, we in the spirit of burlesque and satire have created a new folk hero, with the spirit of the old but the outrageousness of the new.

The originators of the heroes of yesteryear and those who immortalised them on the silver screen and in comic strips played no part in the production of this motion picture, but it could not have been made without them, for their ideas and visions of other worlds have been our inspiration. To those innovators and their fans throughout the world, we dedicate Flesh Gordon.

It should be noted here that there is no suggestion that Lucas was inspired by Flesh Gordon. Lucas began writing his film in 1973, and discussed the project in interviews that predated the release of Flesh Gordon.

But Lucas and the makers of this sexploitation film clearly shared very similar influences, and came to a very similar conclusion — that the time was ripe for these types of adventure stories to make a comeback.

The makers of Flesh Gordon just chose to target their film at a very different audience.

Flesh Gordon was released in the ‘Golden Age of Porn’, when the idea of spending half a million dollars on a sci-fi skin flick and rolling it out to theatres around the country actually made a degree of sense.

In 1970, Graffiti Productions had released Mona: The Virgin Nymph, the first 35mm adult feature film to get a national release in theatres. This, along with Andy Warhol’s Blue Movie – released, appropriately enough, in 1969 – had started a trend of pornographic films that received wide releases and mainstream press coverage, like the infamous Deep Throat (1972) and the critically acclaimed The Devil in Miss Jones (1973) and The Opening of Misty Beethoven (1976).

Suddenly, wholesome celebs like Bob Hope and Johnny Carson were openly talking about porn on television, and in 1973, The New York Times Magazine ran a five-page article on the ‘porno chic’ phenomenon.

Flesh Gordon, then, was Graffiti Productions’ attempt to capitalise on this trend and take it one step further; to create the first pornographic special effects blockbuster.

The film is, to its credit, a remarkably faithful adaptation of that first Flash Gordon serial from the ‘30s, albeit with some heavy innuendo and mild sex scenes thrown in for good measure (the ‘hardcore’ stuff, according to Howard Ziehm’s audio commentary, got left out of the final cut after the negatives were confiscated during a police raid).

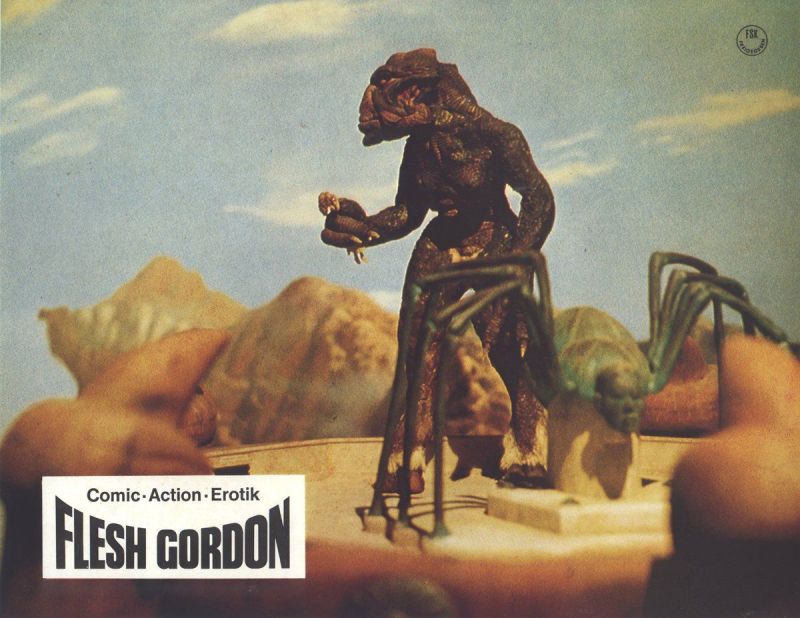

The relatively high quality of Flesh Gordon’s effects can be attributed to the unusually talented crew who worked on the film, including stop-motion experts and young effects artists who would later go on to become Academy Award-winning legends.

Dave Allen and Jim Danforth animated the film’s impressive stop-motion sequences. The two had previously collaborated on 1970’s When Dinosaurs Ruled The Earth, a landmark in stop-motion animation that was eventually given a shout-out in Jurassic Park.

On Flesh Gordon, Allen was responsible for the memorable appearance of The Great God Porno — who was also known as ‘Nesuahyrrah’, a reference to stop-motion pioneer Ray Harryhausen.

The Great God Porno was not intended to have any lines, but Allen’s work made the lumbering monster appear so expressive, dialogue was dubbed to match its mouth movements. (The dialogue was voiced by an uncredited Craig T Nelson, who was unknown at the time, but would later star in TV’s Coach and provide the voice of Mr Incredible in The Incredibles.)

Greg Jein, who would later receive Oscar nominations for his work on Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind and 1941, created miniatures for Flesh Gordon, while Star Trek veteran Michael Minor – who worked on the original series, The Motion Picture and The Wrath of Khan – served as the art director.

Rick Baker, the GOAT makeup artist who helped create the aliens in the Mos Eisley Cantina, as well as the memorable monsters in An American Werewolf in London, Michael Jackson’s Thriller and dozens of other great films, did some of his earliest work on Flesh Gordon.

Even Dennis Muren, one of the first people hired at ILM to work on Star Wars, worked on Flesh Gordon first.

Muren ended up playing a key role in the making of many of Lucas and Steven Spielberg’s best films and winning a total of nine Oscars. He was the first visual effects artist to be honored with a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. If Star Wars had a Mount Rushmore, he would be on it.

But in the early ‘70s, he had one film to his name — Equinox, a midnight movie he had directed with stop-motion effects by Dave Allen and Jim Danforth — and he needed the work.

“On Flesh Gordon, some friends of mine got the job and I came to do some of the modelling work on that,” Muren told Ain’t It Cool News in 2015. “I was on that for a long time shooting miniatures just flying through the air. I was just working with a bunch of friends and by that time all of us younger people in LA, the total of, like, 10 of us or whatever that were doing effects, that was a show we all came together on and got a lot of work. The chance to work for two months and make some money…

“And the show just really grooved. It was originally a softcore porn movie, but my friend Mike Minor got the job on it helping with the art direction and they saw how wonderful the movie was looking and decided to try and turn it into a regular film, maybe an R-rated film or something like that, and they put more money into it. They wanted to add more and more effects to it, and there weren’t that many chances to get to work with 35mm, which all the effects and everything were shot in 35mm."

Flesh Gordon did receive an R classification (rather than an X rating that would have made it a harder sell to theatres), and while it didn’t set the world on fire like Lucas’ space opera eventually would, it did manage to double its $470,000 budget at the box office.

It was even nominated for a Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation in 1975, where it went up against Young Frankenstein, Phantom of the Paradise, The Questor Tapes and Zardoz. (It lost to Young Frankenstein.)

But the film didn’t do well enough to turn big-budget sci-fi porn into a trend, and by the early ‘80s, the rise of home video essentially killed the market of people willing to go to a movie theatre to see sex shot on 35mm film.

Aside from a failed sequel (Flesh Gordon Meets the Cosmic Cheerleaders) in 1989, you’d be hard-pressed to argue the film had a real impact on pop culture.

One person it did have a lasting impact on, however, was title sequence designer Dan Perri.

Perri accepted a percentage of Flesh Gordon’s profits in lieu of an upfront fee, and was badly burned by the experience, vowing never to accept points in place of a fee again.

A couple of years later, he was hired by George Lucas to design the opening crawl of Star Wars.

“Somewhere in the middle of all this,” Perri told Art of the Title in 2015, “while I was still putting it together, [producer] Jimmy Nelson called me up and said, ‘George wants me to ask you, would you be willing to take a half a point of the movie instead of your fee?’

“And I said, ‘Are you crazy? No way in hell! No way!’ So I turned down that half a point to get my seven thousand dollars…”

Flesh Gordon is available on Amazon.

Force Material is a podcast exploring the secrets and source material of Star Wars with hosts Rohan Williams and Baz McAlister. Listen and subscribe on iTunes, Spotify, iHeartRadio, TuneIn, Stitcher, PlayerFM and Castro; stay in touch with us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram; and support the show by browsing our range of shirts, hoodies, kids apparel, mugs and more at TeePublic.